Is Your Last Purchase Worth More, Now That It's Yours?

The concept of depreciation is fairly well-known; most people accept that many goods (cars, electronics, furniture and more) tend to lose value over time. That being said, there are also a few items that tend to gain worth, like houses or fine art. But what about everyday purchases? The answer depends on your perspective. Here's how the role of ownership plays into consumer behavior and valuation of goods.

Ownership Boosts Value...From the Owner's Perspective

According to what's commonly called the Endowment Theory, simply owning something increases its worth–as perceived by the owner. Interestingly enough, this applies to most parts of life. People grow attached to spouses and even their jobs, making them resistant to change. Similarly, we tend to develop an attachment (whether conscious or not) to purchases made and gifts we've received. This attachment and sense of worth is almost immediate–meaning emotional ties and integrated memories aren't the only motivators for perceived value.

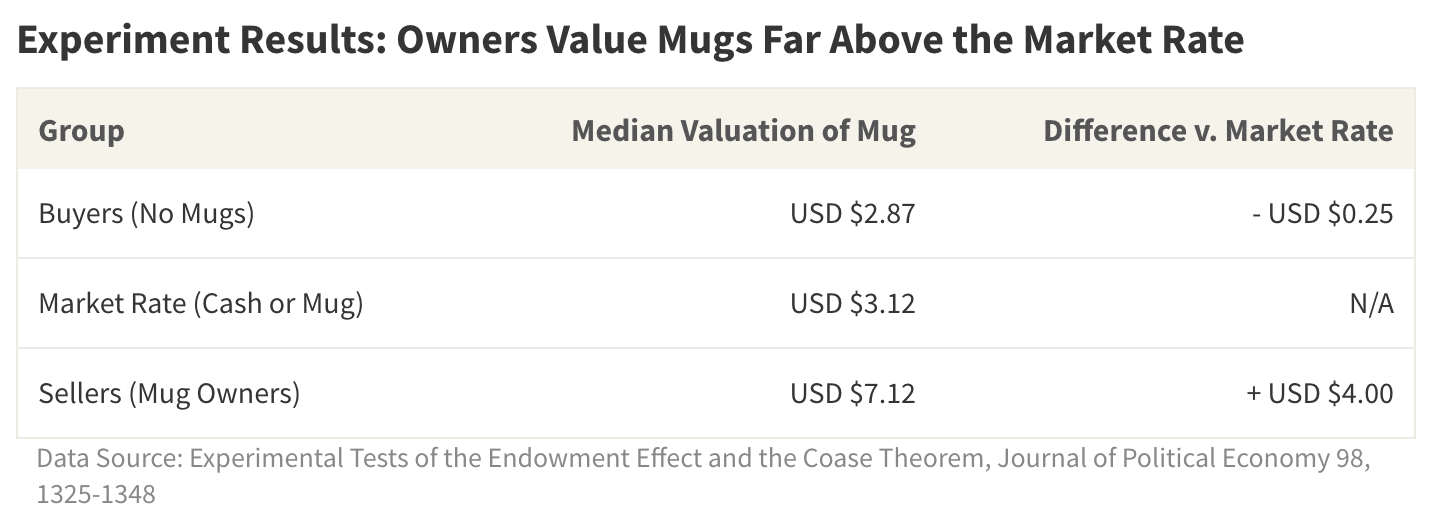

What does this boosted value look like, in real terms? In an experiment by Kahneman, Knetsch and Thaler, people who were given a free coffee mug valued the item at a median price of USD $7.12. However, people who were not given a mug were only willing to pay a median price of USD $2.87. The median worth of the mug, established by a third group, was USD $3.12. In other words, the price that owners felt their mug was worth was more than 2x the perceived market value, and 3x the price buyers were willing to pay.

Considering this information, it's also worth pointing out that buyer expectations are rather close to market value, but owners have price expectations far above the standard. This often results in mismatched perspectives during transactions. Understanding the associated challenges, however, can better build towards success.

Ownership Bias Can Keep You Away From Better Opportunities

We've already established that owning something can make you feel, quite simply, that it's worth more. While this is a great deal if you plan to keep the item, it can prove detrimental if an opportunity to trade or sell arises.

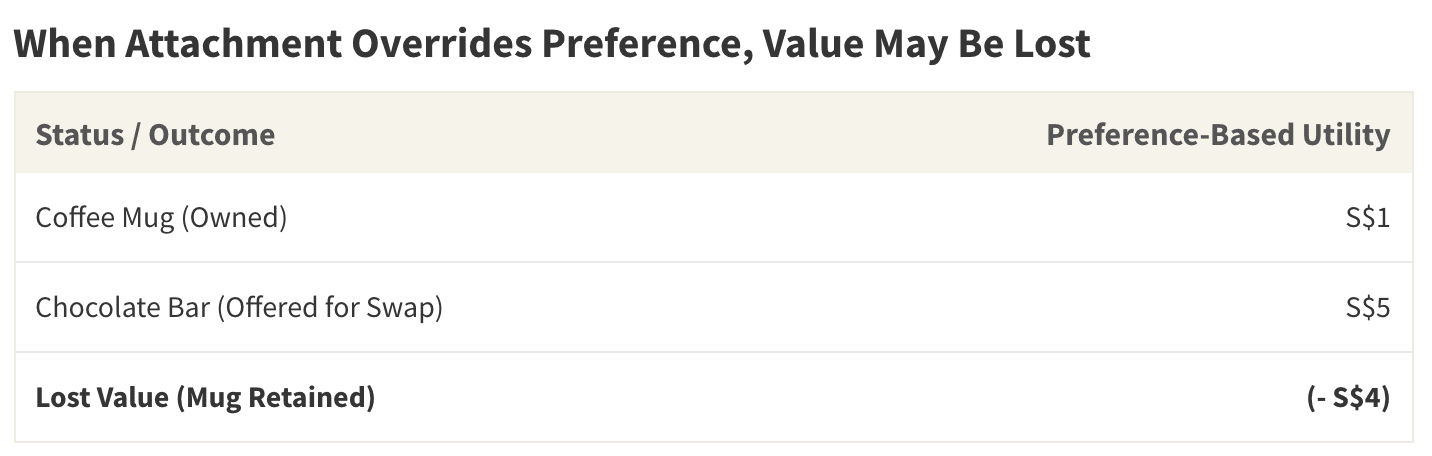

In the first case, the attachments of ownership can stand in the way of actualising on your preferences. Just owning an item can drive an irrational need to keep it, even at the expense of a better opportunity. A perfect example is also found in the discussed study by Kahneman, Knetsch and Thaler. One group of participants was given mugs and another group was given chocolate bars; both items were of comparable value. Next, each group was given the opportunity to swap for the other item–the mug for a chocolate bar, or a chocolate bar for a mug. Given the scale of the experiment, it's expected that participants overall would have a roughly 50-50 split in terms of preference. However, 89% of people in the mug group opted to keep their mugs, while 87% in the chocolate group chose to keep the chocolate.

This indicates that people who naturally preferred the opposite item kept what they were given, even after receiving the opportunity to switch. If this is true, ownership may have actually blocked greater fulfillment. Here's an example in context. Let's say you're a chocolate lover who doesn't often drink coffee. However, you've been given a free coffee mug. You can swap this for a candy bar–but you don't (perhaps without quite knowing why). While you may have an attachment to your mug, you're unlikely to use it and are now missing out on the joys of consuming your favorite treat.

Irrational Attachments Jeopardise Value for Both Buyers & Sellers

Another potential dilemma around ownership involves selling. While ownership does have an immediate impact on perceived worth, time contributes in its own ways as well. Experts posit that people incorporate certain items into their sense of self and personal worth; alternatively, these items may become associated with memories and therefore, linked to our identity. Selling such items, then, can feel like a threat to self.

Unfortunately, this can lead to financial loss. Consider this–perhaps you're currently moving or have decided to tidy up your apartment. You've spent years shopping and accumulating things like home decor and furniture; perhaps you've invested significantly in appliances or electronics that took time to pay off. The sense of attachment you may have with these things can contribute to a heightened sense of their worth. To continue the example, you may have a favorite chair that you strongly feel is worth S$250–and there's no way that you'll sell it for even a cent less. Time goes by, and potential buyers are only offering S$75-S$100. Soon, your move date is around the corner, and you're at a crossroads–do you accept a lower offer, or refuse to accept this devaluation? Even though accepting a low offer can feel like an insult, you may want to keep in mind that not selling yields an even lower reward–S$0.

The troubling part of this scenario is that ownership bias can negatively impact both buyers and sellers. Owners can end up receiving nothing for their prized possessions, especially if their window for selling is finite. For example, refusing to sell your S$250 chair at a discount may mean you lose S$250 value by discarding it, or leaving it behind. On the other hand, buyers (who often have expectations closer to market value) are less likely to make purchases at the elevated 'ownership' rates. By not making the purchase, they lose out on the value the item could have provided to them–like S$75 for your chair. Negotiating to find a middle ground and remaining rational is the best way to reward all parties.

Last Word: Ownership Biases Can Also Have a Social Impact

Finally, ownership biases can go beyond selling personal items. In fact, repercussions can actually influence your social life. For example, identifying an idea or concept as your own can lead to an over-valuation of its worth and make it difficult to move on or listen to others. It's also possible to develop a sense of ownership over a space at home, school, or work that breeds familiarity, and therein drives discomfort with change. Overall, remaining aware of ownership biases is key to rationally evaluating all parts of life.